Although the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is confined to sea-air interactions in the tropical Pacific, it can impact the global climate system by releasing considerable heat into the atmosphere and changing atmospheric circulation. Compared with weak or moderate El Niño events (0.5 °C ≤ Niño3.4 index < 1.5 °C), strong events (Niño3.4 index ≥ 1.5 °C) can induce socioeconomic shock. In 2015/16, a super-strong El Niño event (Niño3.4 index ≥ 2.0 °C) fueled a sharp increase in the global mean surface temperature (GMST), resulting in the highest temperature since 1950 and suddenly interrupting the global warming hiatus since ~2000. This super-strong El Niño also produced widespread drought that severely disrupted tropical crop dynamics and resulted in pantropical wildfires. In boreal summer 2016, El Niño-dominated destructive floods occurred in southern China, causing direct economic losses of more than 313.44 billion RMB and affecting the lives of approximately 100 million people. Therefore, with the end of unusual three consecutive years of La Niña in May 2023 and the onset of El Niño in July 2023 (https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/wmo-update-prepare-el-ni%C3%B1o), there is looming demand for accurate forecasts of the type and intensity of El Niño and early warnings of possible impacts in 2023-2024 to maximize the stability of societal demands and natural ecosystems.

A STRONG El Niño IS PREDICTED TO OCCUR IN WINTER 2023/24

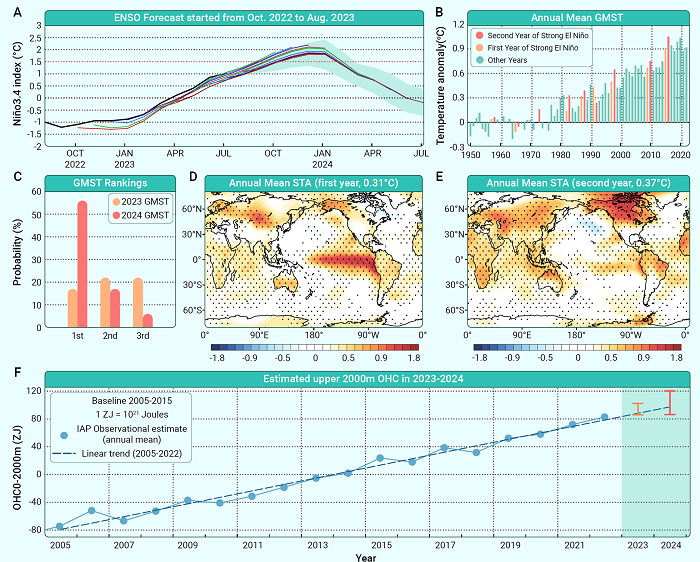

We predicted the possibility of an El Niño event in 2023/24 using the ensemble prediction system (EPS) developed at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS);1 this prediction is supported by westerly wind anomalies in the lower troposphere over the tropical western Pacific and eastward spread of anomalously warm subsurface water along the thermocline, which is ventilated at the surface of the eastern Pacific. The system can achieve good forecast skills with lead times of up to 1 year and excelled at predicting the super-strong El Niño in 2015/16 and the three-year La Niña during 2020-2023. The forecasts made monthly starting from October 2022 to August 2023 (Figure 1A, solid color lines) were consistent with the observations (solid black line). According to the latest forecast starting in August, the warm anomaly is predicted to develop until the Niño3.4 index exceeds 1.5 °C in boreal autumn and may be maintained throughout winter. There will almost certainly be an El Niño event (~100% chance), with 87% of 100 members supporting at least a strong type. The warm SST anomalies are predicted to be located in the eastern Pacific, which is characterized by stronger SST anomalies than those of the central Pacific El Niño and can cause more extremes and more substantial disruptions to ecosystems. However, considering that the current warming signal mainly originate from the eastern equatorial Pacific and that westerly anomalies are not as strong as those of the three previous super El Niño events (1982-1983, 1997-1998, and 2015-2016), the El Niño in 2023-2024 has a lower possibility of being super strong. Meanwhile, the likelihood that the El Niño might be weaker than forecasted should not be ignored because 13% of the 100 members report a weak to moderate type of El Niño.

Figure 1. Climate crises associated with the predicted strong El Niño in 2023-2024

(A) 12-month forecasts of ensemble-mean Niño3.4 index that started from Oct. 2022 to Aug. 2023 made by IAP ENSO EPS (solid color lines), the shading shows the ensemble spread of forecasted Niño3.4 index starting from Aug. 2023, and the black solid line represents the observed Niño3.4 index from Aug. 2022 to Jul. 2023. (B) Annual time series of GMST anomalies during 1950-2022 (Datasets: BEST, GISTEMP v4). The first and second years of nine strong El Niño events are indicated by orange and red bars, respectively. (C) The statistically forecasted probability for GMSTs to be 1st to 3rd in 2023 and in 2024. (D)-(E) Distribution of STAs in the first and second years of strong El Niño composited by the nine events in B. (F) Annual time series of the OHC0-2000m during 2005-2022 (blue dots), the corresponding linear trend (gray dashed line), and the estimated OHC0-2000m in 2023-2024 (red and orange bars) based on linear regression methods with a 90% confidence interval.

The results are consistent with the latest Climate Prediction Center and International Research Institute for Climate and Society ENSO Outlook (https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current/). On August 30, 2023, three tropical cyclones in the northwestern Pacific, including Saola, which has developed into a Super Typhoon, are also potential high-frequency forcings that continuously excite the westerlies and promote El Niño development. How the climate will respond in the remaining part of 2023 to 2024 will be tightly bound to the evolution of El Niño, increasing the need for weather forecasts and seasonal-to-interannual climate predictions to take necessary measures.

ESTIMATED PROBABILITY OF RECORD-BREAKING GMST IN 2023-2024

Considering the leading role of El Niño on interannual GMST variability,2 we analyzed the GMST anomalies in the first and second years of nine strong El Niño events since 1950 (Figure 1B) to examine the potential rankings of the GMSTs in 2023-2024 (Figure 1C). Although the 2023 GMST has a 61% chance of being among the top 3 highest temperatures, the likelihood for setting a new record since 1950 of the 2024 GMST, when El Niño has peaked and decayed, is almost 60%, which is much more significant than that of the 2023 GMST when El Niño is developing. El Niño can affect the surface temperature anomalies (STAs) of continents in the first and second years (Figure 1 D-E), such as by triggering tropical-extratropical and cross-basin interactions, driving Rossby waves, releasing large amounts of heat and water to influence mean-state circulation, subtropical jet, transient eddy, monsoon, cloudiness and downward longwave radiation. Clearly, warming in the first year of strong El Niño is dominated by central-eastern tropical Pacific, with contributions from central Asia and Alaska. However, the anomalous warm signals in the second year expand to nearly all continents, indicating potentially warmer-than-normal climate in 2024. The equatorial Pacific region has less direct impact in the second year because a La Niña typically follows a strong El Niño and can offset the warming signal.

POTENTIAL CRISES ACCOMPANYING A STRONG El Niño IN 2023-2024

Global ocean

According to IAP/CAS data, the upper 2000 m ocean heat content (OHC0-2000m) has reached a new record high in 2022.3 Climate change, negative PDO and three-year La Niña in 2020-2023 jointly enhance the anomalously high OHC in the warm pool region. Due to the continuing effects of global warming, the OHC0-2000m in 2023 and 2024 is estimated to be 3-19 to 4-37 ZJ higher than that in 2022 (Figure 1F). This enormous energy accumulation may not only be a prerequisite for strong El Niño development and extremely high GMSTs, but it can also indicate severe consequences for the global ocean, such as marine heat wave intensification, ocean deoxygenation, and oceanic diversity reduction. A higher OHC also leads to sea level rise through thermal expansion at a rate of 0.75 mm/10 ZJ. In 2023/24, the potentially higher thermosteric sea level along the tropical ocean may induce more storm surges, coastal erosion, and saltwater intrusion, increasing challenges related to engineering design, and coastal development plan modifications.

Crop production

The upcoming strong El Niño may significantly impact global crop yields4 and international agricultural markets in 2023-2024. Due to the severe anomalous temperature, radiation, rainfall and extreme weather triggered by this El Niño, there may be low yield anomalies for maize, rice and wheat crops at the global scale (maize: -2.3%; rice: -0.4%; wheat: -1.4%). However, after the three drought years induced by La Niña, potentially increased precipitation in North and South America, the largest soybean-producing region in the world, may benefit the global soybean yield (+3.5%).

Possibly abnormal climate events in China

China may have to face many abnormal climate events in 2023-2024. The western North Pacific anomalous anticyclone (WNPAC) excited by the upcoming strong El Niño can generate anomalous southerlies to suppress the winter monsoon, making China experience an abnormally warm winter in 2023 in most regions and possible extreme drought over North China in spring 2024. The weakened winter monsoon is not conducive to the diffusion of fog and haze, increasing the probability of air pollution. The consecutive impact of the WNPAC could maintain until summer 2024, assisting the summer monsoon in transporting moisture and moist static energy, greatly increasing the risk of extreme precipitation and floods in South China.5

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, CAS (Grant No. ZDBS-LY-DQC010), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42175045).

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

[1]Zheng, F., and Zhu., J. (2016). Improved ensemble-mean forecasting of ENSO events by a zero-mean stochastic error model of an intermediate coupled model. Clim. Dyn. 47, 3901−3915.

CrossRef Google Scholar

[2]Tung, K., and Chen., X., (2018). Understanding the recent global surface warming slowdown: a review. Climate. 6 , 82.

Google Scholar

[3]Cheng, L., Abraham, J., Trenberth, K.E., et al. (2023). Another year of record heat for the oceans. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 40, 963−974.

CrossRef Google Scholar

[4]Iizumi, T., Luo, J., Challinor, A., et al. (2014). Impacts of El Niño Southern Oscillation on the global yields of major crops. Nat. Commun. 5, 3712.

CrossRef Google Scholar

[5]Liu, F., Gao, C., Chai, J., et al. (2022). Tropical volcanism enhanced the East Asian summer monsoon during the last millennium. Nat. Commun. 13, 3429.

CrossRef Google Scholar

ABOUT THIS ARTICLE

Cite this article:

Li K., Zheng F., Cheng L., et al., (2023). Record-breaking global temperature and crises with strong El Niño in 2023-2024. The Innovation Geoscience 1(2), 100030. https://doi.org/10.59717/j.xinn-geo.2023.100030